Stimson Bullitt

lives and legacies

contents:

encomia:

1. Herb Altschull on the KING era

2. Michael Roemer eulogy

3. to David Brewster from fred nemo

4.

climbers' tributes

writings:

5. Antiquity in the Midwest

6. Stim's introduction to William Dwyer's Ipse Dixit

7. Respect: African Americans vs. Native Americans

8. photographs

9. Roethke

By Herb Altschull

A word about a man who hated television. He thought it was an abomination but I salute him as a great figure in television and the best boss anyone could ever dream of. I write of Stim Bullitt who was, for ten years from 1961-71, president of the KING Broadcasting Company. Oddly, he scorned the media.

To give him his complete name it was Charles Stimson Bullitt, but nobody ever called him that. He was an intellectual, an anomaly among broadcast executives, and a Democrat, which is almost an anomaly. He was an inveterate outdoorsman who once scaled 20,300 feet to the top of Mount McKinley - in his 60's. Moreover, he was an essayist, with a gentle manner and a ferocious wit. He was a staunch devotee of Scott Fitzgerald and Hemingway.

A modest man, he discarded praise and said that the only list he ever wanted to be on was Richard Nixon’s enemies list. That was a designation he was proud of. As head of King Broadcasting, Stim became the first TV executive to write editorials opposing the war in Vietnam. I helped him write that editorial and many of the others that stirred the wrath of the business establishment - and companies that provided commercial support to KING.

I was lucky, very lucky, to have arrived on the scene at the start if his tenure at KING. I had come to Seattle from the East Coast where I was toiling, unknown, among the many would be influential reporters and commentators in the burgeoning broadcast industry. I had applied to KING among many other outlets and was astonished to be invited to Seattle for an interview. Stim was looking for unusual hires who had no particular credentials other than eagerness to serve for what he thought was a Good Cause. He and his right hand man, a Democratic politico from Oregon named Ancil Payne, did the interviewing at Stim’s family.

I got the job in part because Stim was impressed that I recognized the Mozart concerto playing on his phonograph. How could a job seeker on TV recognize and identify a Mozart concerto? Over the years Stim and I shared many moments listening to great music. What an introduction it was for me, a devotee to classical music, to a television tycoon. I thought they were all musical illiterates. I expected Stim and Ancil Payne to be devotees of the Beatles, who were the rage in 1963.

And what a job I was offered! I could cover any story I wanted to and tell it in my own words. At the Associated Press, where I had been employed, the myth of objectivity was king, so I could take no position on anything. Right at the start I tackled two controversial themes, railing against the Vietnam War and the racial situation in Seattle.

Those positions brought me close to Stim spiritually. It was 1967, and on Capitol Hill where Stim lived not a Black face could be seen. On the TV stations not a Black face could be seen. On the radio stations not a Black voice could be heard. Off we went. I did commentary on the racial situation and Stim wrote editorials. His was the first editorial in the country in support of blacks moving into white neighborhoods.

With those two stands I won national awards, and the reputation of KING-TV began to soar under Stim’s leadership. We went on to support all the good causes. I was in journalism heaven, and KING was embarking on a record that few stations could achieve. We endorsed equal housing; we pushed for enhanced educational opportunities for city and state. Stim’s was the first editorial voice to speak out against the Vietnam War in the country and I won an Emmy for my report.

During this period Stim and I became fast friends settling all the world’s problems over lunch. I never had to plead for money. In an industry where Money is everything Stim never hesitated to risk financial support for things he believed in. I had the opportunity to learn the broadcast industry from top to bottom. Our reputation grew all the time and I loved what I was doing. I did a 15-minute radio broadcast daily called “Perspective” and a three to five minute insert in our evening TV news show.

Probably our most ambitious undertaking was “Color Me Somebody.” One of my major interests was in the racial situation in this sea of whiteness. In my conversations around the area with people who didn’t realize the racial undercurrent in this city I had always, from the beginning, wanted to use my position and KING's to further the cause of racial equality. This was a cause worth fighting for, and I knew Stim wanted to lead the fight. I proposed that we do news shows and documentaries, and to my delight Stim was prepared to get in front of the campaign.

It was the most expensive project that KING had ever undertaken, but Stim approved every dollar that I and my colleagues wanted to spend. We hired a black camera man named Gil Baker and a black secretary named Martha Hubbard to work with me in identifying a block in the Central area where blacks congregated; and, together with Jim Compton, who later became a Seattle City Councilmember, we identified the block and I went about interviewing all the residents.

We churned up hours of recorded interviews which I later edited into a narrative for a broadcast. The “Color Me Somebody” quote came from an interview of Ed Pratt, who wound up being murdered before the documentary could air. When the 90-minute documentary was broadcast, it became my greatest achievement in broadcasting and I think it made Stim proud. The show later was trimmed to 60 minutes for nationwide broadcast on public television.

Stim was a man of many parts. He also sank lots of money in a print campaign promoting Seattle Magazine, a labor of love about social, economic, and political issues. For the magazine I undertook a monthly column on Seattle newspapers and other media, which I called “The Press Club.” My approach was to beat the newspapers over the head for their timidity.

Everything Stim did was to further the city of Seattle. While he was a businessman, these public interests always trumped money, and he would be fearless in campaigning for things he believed in. One issue stands out in my mind. In some of the interviews that I collected for “Color Me Somebody,” two of the black people who had worked for Boeing unabashedly criticized the company as not being an equal opportunity employer. When I played that part for Stim I didn’t know how he would react; and, at my suggestion that he might want to cut that sequence out, in order not to offend the mighty Boeing, his comment was: “That's what he said. Let’s leave it in.”

As said: the best boss you could ever want.

Herb Altschull worked for many years at King Broadcasting, as a commentator, documentarian, and reporter on radio and television.

(from crosscut.com)

2. mike roemer on their friendship

In our boarding school there was a married couple who essentially adopted me. After I left England, their letters to me and my family always began with: “My Dears – ”.

When I thought about speaking with you this morning, “My Dears – ” were the words that came to mind. For years I have thought of you as my second family, and you are very dear to me, even those who are not here.

If, in speaking about Stim, I also speak about myself it is because there was something deep down in both of us that created a bond far more significant than the obvious differences in our background and biography.

We seemed to recognize each other before we had time to exchange more than a few experiences, thoughts, and feelings.

We never spoke about this secret likeness, though we talked freely about everything else. But I believe that was why we so quickly understood and cared for each other.

*

Of course Stim had an extraordinary gift for friendship attested to by his many friends in so many walks of life. Indeed, I am sure he was the kindest, most loyal, and most honorable friend many of us will ever have.

But today I shall go in a different, more personal direction – one he himself might find a little uncomfortable.

He and I were both raised in a context that did not allow our feelings easy expression.

In the England of my childhood, families that were expected to raise leaders – in government, the military, science, the law, and commerce – sent their boys to boarding school at a very early age. Many were no more than eight when they were effectively exiled from homes where, though their parents were preoccupied or even absent, they were cared for by often kind and tender nannies. (Churchill kept a photograph of his nanny in his bedroom throughout his life.)

The schools were emotionally and sometimes physically cold, without room for kindness, fellow feeling, or any satisfaction not connected with achievement – most often of the athletic kind involving pain and the ability to endure it.

Feelings were largely taboo and associated negatively with women, since they would interfere with exercising authority and making hard decisions affecting the lives and sometimes deaths of others.

Most of the boys sent to English public schools adjusted and thrived. But anyone more sensitive, anyone with a literary or artistic bent, would be pressured to stifle that side of himself. When Shelley was a student at Eton, there was an afternoon sport called “Shelley-hunting”. It seems to have involved hordes of yawping students chasing down a sensitive child, who had hidden in fear. It was tolerated or even encouraged by the staff because presumably the vulnerable qualities of little Shelley would be frightened out of him. There is no way of knowing how many children were made permanently miserable by this kind of treatment, but in Shelley’s case – fortunately for English poetry – the regimen didn’t work.

Though this approach was applied most consistently and deliberately to males in the upper class, it pervaded the values and decisions lower down on the social scale. Nor was it absent in my own upbringing in the Berlin of the 1930’s. Needless to say, it migrated to the United States with British settlers, and served American society effectively, if not kindly, for several centuries. I ran smack into it when I came to the States in 1945 and went to a college deeply imbued with the Anglo-Saxon tradition, both in the generative and the restrictive sense.

*

I believe both Stim and I were somewhat atypical products of this heritage.

But while neither of us fit perfectly into the expectations our communities had of boys, unlike Shelley we didn’t resist adaptation completely; no one in our respective schools went hunting for us in the afternoon. I think we were both secret misfits, but – perhaps because we were neither strange enough nor sufficiently self-confident to be indifferent to what others thought – we compromised. We met the expectations of our communities halfway by burying – or at least hiding – essential parts of ourselves.

Prominent among them would surely be feelings of tenderness and vulnerability that men, even today, are expected to confine to the four walls of their homes. Everywhere else they tend to get in the way of doing your job, even if it is no more specialized than driving a bus.

If you are a sensitive male with strong feelings who has been told over and over that your sensitivity and empathy undermine what is expected of you, it can become difficult for you to give them expression even at home. You may be able to show them at times, but not consistently – for always gnawing at you is apt to be the guilty conviction that the time and energy you spend on personal relationships and satisfactions betray the privileges you have “enjoyed” (or have been told you enjoyed – I hardly remember enjoying mine). Personal relationships and family happiness are of but marginal interest to the community. The task for which your privelege has shaped you is in the public and not the private arena.

I recently ran across a love poem by Richard Lovelace that said:

I could not love thee, Dear, so much

Lov’d I not Honour more.

Most of us would agree that even the most private and intimate of our relationships are ultimately subject to communal approval and rules. Without them, no young man could be persuaded to leave his wife and children to serve in a distant war.

But most of us are not expected to pay the steep price that someone like Stim had to pay to uphold an abstraction like Honor. For him it wasn’t an abstraction, but a living reality – one he had to pay for personally every day, often with the currency of private happiness that most of us take for granted. I am painfully aware that you – his family – were, like my own, not free to step away. You had no choice in the matter but were part of his life and commitments. All I can say to you, as I did to my own children and to my wife, is that he, in turn, had little choice of his destiny. Some people have to give their lives to Honour, or Truth, or any of the other abstractions that govern society, so that they may be real to the rest of us, who need to think about them only in the clutch.

*

I have often thought what a convenience it would be if life were like a restaurant menu that told us exactly what a particular course of action would end up costing us and those closest to us. But inevitably a great deal of what we think, feel, and do is decided for us by the community – and its executive branch: the family – with little input from us as individuals.

Like most good citizens, stim and I tried to meet the expectations of community and family – in his case, not only heading a major enterprise but continuing a tradition of public service. Moreover, as we were expected to do, we passed our own mind-set on to our children. Since we were measured by standards of high achievement, that’s how we often measured others; and since we were hard on ourselves, that’s what we expected of them. Not for us the satisfactions and happiness of simply raising a family. We hadn’t been raised that way and, indeed, hardly knew what was involved.

*

From the beginning of our friendship I was aware of the constraints that Stim’s position as the male head of an illustrious family molded in the Anglo-Saxon tradition imposed on him – a position that, ironically, a great many people envied, since they saw only the privileged and seemingly glamorous surfaces of his life.

Stim took the obligations placed on him very seriously, even when they were in painful conflict with who he was at heart and who he would have much preferred to be.

We all know that his real love was for the law that his father’s side of the family had practiced for so many generations, and he took on his very considerable business and administrative obligations out of a deep sense of duty. He loved literature and wrote eloquently and with great sensitivity, but had to pursue that, too, in his spare time. Perhaps it was in writing, in his use of language, that his deep feelings found expression before he could show them consistently in his personal relationships.

I don’t know of another man who succeeded as well as Stim did in keeping the often diametrically opposed parts of himself in some kind of balance. I could never have done it. At times it inevitably left him self-divided and in conflict.

*

So far I have spoken only about the limitations and constraints the community into which he was born imposed on him.

But of course it also installed deep values and virtues, values and virtues I have seen many times in every member of his family.

He was the bravest, fairest, most honorable, and most deeply democratic person I have known, and the one with the most consistent belief in and commitment to reason.

*

He showed extraordinary courage not only in taking difficult positions long before they became widely accepted, but in facing himself – especially in the last decades, when he felt finally freer to allow the deep tenderness and unfailing sympathy for those in trouble and in pain that was always at his core to come to the surface.

I am sure we all saw Stim, who had great difficulty being personal – yet clearly had an urgent wish to be so – find his way to speaking directly and with deep feelings. Perhaps because I was at a distance and not part of the Seattle community, I got to see it more often. He may have felt less exposed.

Early on, he allowed me to become aware of his deep need to connect – not just to cross the divide between himself and others but to bridge his own inner conflicts and divisions.

*

All of us were aware that in his own eyes he was never accomplished or extraordinary enough.

In mine he was – absolutely.

Had he focused on just one or two instead of the four or five different endeavors in which he distinguished himself, he could have easily attained the highest distinction. I know that performing any of the additional tasks he set himself beyond those imposed by his heritage would have left me an utter wreck.

We know that though he loved and enjoyed life, he was often unhappy and dissatisfied with himself.

Yet I never had any doubt he was the very hero he dreamed of being, and always felt he failed to be.

A hero, moreover, in the deeply human sense, forever trying to resolve the contradictions into which – more poignantly than anyone else I’ve ever known – he was thrust at birth.

*

I join you – his family and his friends – in love and gratitude for the time he was among us on the earth that was so dear to him.

~ June 14, 2009

3. notes to david brewster for his eulogy, from stim's son fred:

A couple of further thoughts:

As his philanthropy has been mostly hidden, so also the ramifications of his vocations as parent, thinker, and conversationalist. These should compete with his prowess as a climber and businessman in the public consciousness. As the significance of his business successes and alpine ascents resides in the gifts he brought to them - the seriousness of his determination, care, and daring; seemingly effortless sealing of friendships; and sheer glory in the work at hand - so with his other lifetime preoccupations.

He read aloud to the six of us Austin, Conan Doyle, Conrad, Defoe, Dickens, Dumas, Hardy, Hemingway, London, Melville, Stevenson, Wells, and Verne when we were very young, and when to be quite the hands-on dad was not remotely the fashion. We made him read The Count of Monte Cristo to us twice - do you know how long that is? He sat me in his lap and taught me Latin and geometry starting age 7 (I conjugate to this day). The five of his kids are in our 50’s and 60’s now and all are lifetime philanthropists, thinkers and ethicists, with equivalent legacies of public commitment.

He was a thinker. Not an art in itself much sung. All those workouts, boxing championships, motorcycle and boxcar trips, tennis matches, ski races, bicycle commutes, sailing marathons, hikes and ascents, and, finally, the climbing-gym, weren't, I'd dare suggest, primarily for the gazing at ineffable beauties or the testing of his considerable limits - those were the bonuses - but for the solitude in which he could think. He loved thinking. It sounds stupid, but he thought everyone should think. He always made you think. To him freedom of thought was more than a right, it was a constitutional duty. Spending quality time in thought fed his civic passions and enabled him to negotiate terrain whose ruggedness dwarfed that of his most harrowing alpine ascents.

(You might have seen the Thomsett Dictionary of Political Quotations in which he's lavishly represented. Other than the raves for To Be a Politician 50 years ago, that's the only print acknowledgement of his intellectual gifts I think I’ve run across. (He was ever between the pincers of the Times and P.I., of course)

Conversation is the most subtle instrument of influence. Ask any FBI – definitely not CIA – interrogator. It’s so wrong that it gets such negligible cred. He liked to recount how, sometime after his own father’s death, a distinguished family friend remarked to him that his father had been the most engaging conversationalist he’d ever known – not too remarkable in a man FDR wanted to head the Department of the Interior, who virtually created the state Democratic Party - but it’s nice to be told. In turn, he loved being told in recent years that by all accounts he seemed to be comfortably filling those shoes.

He was mostly covert in his giving because he took the extreme position that using ideals as advertisements for oneself kind of obviates them. Most importantly, his philanthropy went far beyond his (profligate) gifts of cash, stock, land, and institutions. His lifelong personal and legal advocacy for minorities, the environment, peace, good governance, education, and civic planning are what are central to his philanthropic legacy. More often then not his public stands in these areas came at exhorbitant personal cost.

On reading in the press that he died happy, "gazing out at the mountains he loved," my brain's immediate reaction was, "No. He died happy knowing Obama was elected." I think what my indisciplined brain was trying to convey was that there was something in his life and thought that trumped his love for our stupendous planet, even his love for his devoted family and friends, and that was an implacable adherence to the democratic ideal.

The last time I spoke to him, he was given to repeating himself, but he took best advantage of his alzheimers and mostly confined himself to reiterating things that bear repetition, most memorably a construction of Justice Brandeis' version of his friend Zimmern's translation of Pericles' words out of Thucydides:

“The secret of happiness is liberty and the secret of liberty is a brave heart.”

Excuse such a long and boastful letter,

fred

5. from www.stimsonbullitt.com :

AMERICAN SETTLEMENT - COMMUNITY NAMES

As the line of settlement moved westward across the Continent, why were so many more communities between the Appalachian divide and the Mississippi, than on either side of that territory, given names from classical antiquity and Biblical places? A check of the atlas shows the following in that territory with, by contrast, only a handful on the eastern coastal plain (e.g., Augusta) and west of the Mississippi (e.g., Moab, Olympia, Phoenix).

17 Lebanon and Sharon

16 Athens

14 Troy and Bethel

12 Alexandria and Augusta

11 Hebron

10 Rome and Carmel

9 Canaan, Palmyra, Philadelphia and Shiloh

8 Aurora, Bethlehem, Sparta, and Zion

7 Phoenix

6 Carthage

5 Bethany, Cairo, Corinth and Egypt

4 Ararat, Damascus, Jordan, Naples, Smyrna and Tabor

3 Antioch, Gilead, Jericho, Lydia, Macedonia, Memphis, Rehoboth, Syracuse and Zebulon

2 Berea, Cicero, Cincinnati, Hermon, Joppa, Manassas, Nineveh, Persia, Rhodes and Sidon

1 Babylon, Beersheba, Calvary, Crete, Delphi, Galilee, Gaza, Gilboa, Jerusalem, Mizpah, Moriah, Nazareth, Noah, Palestine, Phoenicia, Scipio, Thebes and Tirzah.

Before about 1790, when settlers started pouring past the Appalachians, through the Cumberland Gap, along the river system to the Great Lakes and so forth, people felt themselves more attached to the Mother Country, felt less conscious of being in a country of their own, so named their communities after the places from which they had come ("New ____"), along with the Indian names that were applied from coast to coast, and sometimes a leader (Williamsburg, Elizabeth). By the late 18th Century, when communities started to be named west of the range near the coast, the settler-namers felt more like Americans, felt less need to connect to the old country, and, in harmony with having created a new country, felt more inclined to express ideals.

Then why were the classical and Biblical sources largely dropped west of the Mississippi? Perhaps a drop in the educational level of community founders? Perhaps some early stages of the shift from private to public education, with less emphasis on the classical? Perhaps a recognition of overuse of classical and Biblical names on the land behind. Most likely may be the shift in attitude toward Jacksonian equalitarianism, disdaining the classical and Biblical as elitist.

6. introduction to justice dwyer's Ipse Dixit:

- from google books

7. from stim’s 1975 indictment of regressive u.s. policies towards indians:

An argument for current policies might be conceivable, despite their violation of American principles, if only they succeeded. But they have been applied for long and have failed.

American Blacks have done better though treated worse. Although the Indians' tribal organizations were battered, with some tribes extirpated and others disbanded, many remain as corporate entities, and most Americans with significant fractions of Indian blood know their tribal ancestry. Many in the west still live on the lands where their forebears roamed. By contrast, the Blacks' tribal organization was disintegrated before they arrived. Not only does no tribal identity remain among them, Blacks have lost knowledge of their distant ancestors' tribes. Most American Blacks having been descended from people living here for as many generations as the Bible records from David back to Abraham, regard themselves, understandably, as authentic Americans.

American Blacks have inherited almost nothing from ancestral tribal connection, or by reason of race. Black men were called "bucks," not "braves." No image of a Black man has been put on our coins. White Americans do not disclose with pride that they have a Black ancestor as they do of an Indian. Non-Black Americans have not named children after admired Blacks, as they have for admired Indians, as did the parents of William Tecumseh Sherman. Orations have not hailed the noble Black man. Poets have not written in honor of Black leaders, as Whitman did of Osceola and Longfellow of the imagined Hiawatha. No Black names were given to cities (Seattle, Pontiac, Keokuk, Osceola, SingSing, Red Cloud), counties or states. No sports teams were named the Washington Blackskins or the Dartmouth, Cleveland or Stanford Blacks. No fraternal order of Blackmen was formed. No popular song was called "Negro Love Call." Not until recently have some white youths chosen Blacks among their heroes, yet for centuries some Indians (e.g., Uncas, Logan) have been idealized as heroes among non-Indians. No one speaks the African counterparts of leaving the war path for a powow to make medicine, smoke a peace pipe, bury the tomahawk and feed the pappoose. Some settlers whose character and ability were admired by the others thought well enough of Indian life to go and live among them (e.g., Sam Houston). Yet despite all that, why have Indians achieved so little in American society in contrast to Blacks, who impressed the settlers so much less? Was Parkman right in characterizing the Indians as resembling stone in being hard but brittle? How far is the difference attributable to public policies?

Yet despite - and indeed because of - the effects of these policies, customs and attitudes, Indians have remained alien to the rest of American society, many apathetic, without ambition, health or hope, while among all national societies without a Black majority, in ours Blacks now take the largest part in significant responsibilities and roles. Among identifiable groups, perhaps none but the Puritans has exceeded Blacks' contributions to American culture in the field of personal style (On that scale, the cowboy of myth may come in a distant third.)

8. photographs

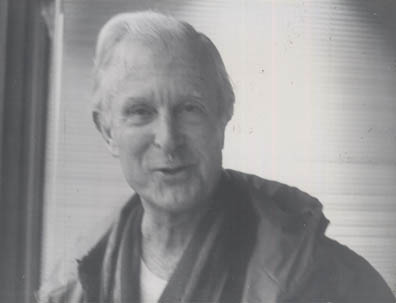

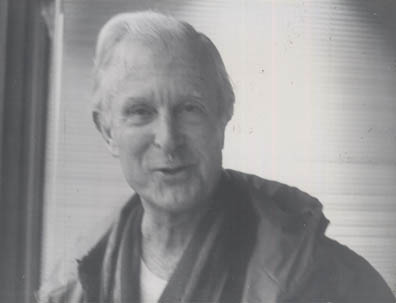

Stim:

1928 ? ?

![]()

at Leyte 1944 with eddie cotton 1950's 1956

Parents and sisters:

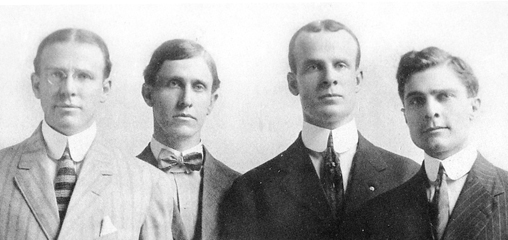

patsy, stim, dorothy s., and harriet bullitt 1928

scott, harriet, stim, dorothy, and patsy bullitt 1928

Wives:

tina hollingsworth bullitt kay & dorothy bullitt, makaiya bullitt-rigsbee, margaret & jill & ashley bullitt 2007

front: dorothy, margaret, ben back: stim, kay, jill, jacques collins 1964 with carolyn kizer 1948

Friends:

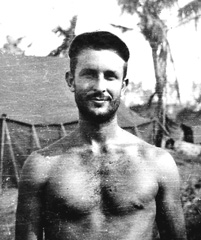

mike roemer & david rigsbee with alex bertulis 2007 bill dwyer

sally, chuck, pete, and john goldmark with homer harris 2002

jim wickwire with shelby scates and bill sumner on denali 1981 virginia and bagley wright

solie ringold, fred nemo, ken macdonald 1984

Kids:

ashley bullitt 1958 ben bullitt 1981 jill bullitt 2007 with dorothy 2008

with shelly, miranda, grady, and chance hollingsworth fred nemo 1950 margaret bullitt 2009

Grandkids:

crystal & melita bullitt 1976 walker schwartzman, ben schmechel, emma schwartzman, makaiya, stefan schwartzman 2009

crystal & melita bullitt 1976 walker schwartzman, ben schmechel, emma schwartzman, makaiya, stefan schwartzman 2009

prairie rose zelano 1991 makaiya bullitt-rigsbee 2007 conrad schmechel 2010

crystal bullitt 1985 melita bullitt 1989

Great grandkids:

cyrena graham 1997 mercedes bullitt 2008 keeshawn penn 2007

Cousins, etc:

marshall, jim, scott, and keith bullitt c. 1900 jacques collins 1968 hank bullitt 2007

photo credits:

stim - fred

stim

1928 - dorothea lange

?

?

at leyte - ?

with eddie cotton - ?

1956 - ?

parents & sisters

patsy, etc. - dorothea lange

scott, etc. - dorothea lange

wives

tina - bill sumner

kay, etc - ?

with dorothy - bill sumner

with carolyn kizer - seattle times

friends

mike & david - david

with alex - cliff leight

bill - ann yow

goldmarks - ?

with homer - seattle parks foundation

jim - john roskelley

with shelby & bill - unknown

wrights - ?

sollie, etc. - ?

kids

ashley - ?

ben - ?

jill - david

dorothy, etc - ?

hollingsworths - ?

fred - mabel kizer

margaret - ?

grandkids

crystal & - fred

walker, etc - ashley

prairie - ?

makaiya - ?

conrad - ?

crystal - fred

melita - fred

great grandkids

cyrena - fred

mercedes - ?

keeshawn - fred

cousins, etc.

marshall, etc. - ?

jacques - ?

hank - hernando castro-rivera

9. unpublished ted roethke poem, after trouncing stim at badminton

Now why do I carry on like this,

And freeze my soul to paralysis?

Why, doctor, it's pure self-analysis

- I really want to be him, be him

I really want to be him.

The situation is sexual:

With money I'm ineffectual;

He's a real, I'm a fake intellectual

- So I want to be like old Stim Stim

I want to be like dear Stim.

Now get this straight: I'm no bigger lover

I've always wanted a younger brother

A home and a rich powerful mother

- So I could be a little more like Stim, like Stim

Just a little more like Stim.

He isn't, like me, an aging lecher -

Whom the Lord Himself wouldn't have made dog-catcher

With that first wife - may the Devil fetch

And fling her to hell. And I'll bet you

- We'll be calling him Senator Stim,

We'll be calling him Senator Stim.

~ from River Dark and Bright